Court Structure

Introduction

The early court system in Illinois was based on the English common law. William Blackstone attributed the source of common law to judges’ decisions handed down from generation to generation. The common law was “general custom” and relied on precedent. The colonists brought the English common law with them to the New World and adapted it to suit their needs. After the Revolution, American lawmakers continued the common law tradition. The United States Congress imposed the common law on federal lands including the Northwest Territory, and trans-Appalachian emigrants carried the law with them when they settled in the areas that would become the states of Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois.

The area that became the state of Illinois operated under the laws of the Northwest Territory until 1800, when the United States Congress created the Indiana Territory, which included Illinois. Congress created the Illinois Territory in 1809 by separating it from Indiana.

For the first few years of the territorial period, Illinois simply used the court system that had existed in Indiana. However, some of these courts, such as the court of common pleas and the general court, had overlapping jurisdictions. By the mid 1810s, the Illinois Legislative Council abolished courts that had been inherited from Indiana and created a circuit court system and appellate jurisdiction in a Court of Appeals for the Illinois Territory.

When Illinois became a state in 1818, the state constitution provided for the establishment of a judiciary system. Illinois operated under this constitution for thirty years. Excessive legislative control over the judiciary system in the state was one of the reasons for a state constitutional convention in 1847. In that convention, delegates passed a new constitution, which completely restructured the judicial system.

Illinois Supreme Court

The 1818 constitution gave judicial power to one supreme court and to other inferior courts that the Illinois General Assembly might establish. The Illinois Supreme Court had original jurisdiction in cases relating to revenue, mandamus, and impeachment, and had appellate jurisdiction in all other cases. The court consisted of a chief justice and three associate justices, who served during good behavior and could be removed only by impeachment. The general assembly appointed the justices and had the power to increase their number. Neither the constitution nor the general assembly required specific qualifications of residency, age, or experience.

Illinois followed the federal precedent that required supreme court justices to travel their home circuits and required appellate justices to hold court in the various counties that comprised a circuit. During the thirty-year period of the first constitution (1818-1848), the general assembly frequently alternated between requiring justices to travel the circuit and appointing separate circuit judges.

In March 1819, the first Illinois General Assembly provided for two terms of the supreme court per year. The supreme court held its first term in December 1819 in Kaskaskia, Illinois. After the state capital moved to Vandalia, the supreme court held court there beginning with the December 1820 term. In 1824, the general assembly increased the appellate jurisdiction of the supreme court to hear cases from any inferior courts that the legislature might create. From 1827 to 1835, the supreme court held court only once per year. In 1835, the legislature again provided for two terms per year. In July 1839, the supreme court held its first session in Springfield, the new Illinois state capital.

In 1839 and 1840, the Whig-dominated supreme court made two decisions (Field v. People ex rel. McClernand and Spragins v. Houghton) that displeased the Democratic majority in the legislature. In 1841, the Democratic-controlled general assembly added five new justices, all of whom were Democrats, which gave the Democrats a six-to-three majority on the court. Each of the nine justices traveled the circuit in which he lived. In 1843, the general assembly again reduced the number of terms the supreme court held to one per year.

The legislature added a new type of jurisdiction to the supreme court in 1843. In a circuit court case, the litigants could form an agreed statement of facts that contained points of law at issue between them. One of the litigants assigned errors in the case, and the supreme court heard the case as any other appeal. A circuit judge could also certify any question of law at trial then forward the issue to the supreme court as long as the litigants agreed to it. Likewise, the litigants could also certify questions of law. The supreme court ruled on the question of law only, then the case returned to the circuit court for final disposition. Neither the agreed case nor the certified case applied to cases in which title to real estate was in question.

The new constitution of 1848 reduced the size of the supreme court to three justices and divided the state into three grand divisions. Qualified voters in each of these divisions elected one supreme court justice for a period of nine years. The legislature provided for staggered elections to elect one justice every three years. The justice with the longest tenure became the chief justice. A justice of the supreme court had to be a citizen of the United States, had to reside in Illinois for at least five years and in their respective grand division for at least two years, and had to be at least thirty-five years of age. Each grand division held one annual term with the first division in Mt. Vernon, the second division in Springfield, and the third division in Ottawa. The divisions were also referred to as the southern, central, and northern grand divisions, respectively. Appeals went to the grand division that contained that county circuit court. Two justices formed a quorum and needed to concur for a decision.

Supreme court officials included clerks, deputy clerks, attorneys general, and reporters. The justices appointed a clerk to document proceedings and to preserve complete records of all the decisions of the court. The clerks could appoint deputy clerks to assist them in their duties. After the change in the supreme court in 1848, each of the grand divisions had its own clerk. Qualified voters in each division elected a clerk for a term of six years. The attorney general prosecuted or defended cases in the supreme court in which the state of Illinois was a party. The first Illinois General Assembly provided that the supreme court publish reports of the cases. The court appointed a reporter, who was “learned in the law,” to gather opinions from the justices, to write summaries for the cases, and to publish the reports. There was no executing officer of the supreme court. The justices sent writs to county sheriffs. Eventually, the sheriff of the county that contained the state capital (Fayette and later Sangamon) became the sergeant-at-arms for the supreme court. After 1849, Jefferson and La Salle County sheriffs performed the same duties for the supreme court in the first and third grand divisions.

Circuit Courts

In 1819, the first Illinois General Assembly created the circuit court system. The legislature divided the state into four circuits and assigned a justice of the supreme court to each circuit. Justices held terms for each county of the circuit court twice a year. Justices rode their respective circuits in order to hold court at each county seat and to remain in close contact with the citizenry. The circuit court had jurisdiction in all cases at common law and chancery arising in each of the counties in the circuit where the debt or demand exceeded $20. Circuit courts also had jurisdiction in all criminal matters committed within any county in the circuit. While holding circuit court, the justices were conservators of the peace and had the power to issue injunctions and writs.

Several counties comprised one circuit. All circuits had a spring term and a fall term. Populous counties, such as Sangamon, often had third terms. When court concluded in one county, the circuit judge, the state’s attorney, and several lawyers traveled to the next county in the circuit. They repeated this process for each of the counties within the circuit. The individual court terms lasted from two days to several weeks, and the circuit terms usually lasted two to three months.

In 1824, the legislature created a fifth circuit, relieved the supreme court justices of their circuit duty, and appointed five circuit judges to hold court. Each circuit judge had to live within the boundaries of his circuit. An 1827 legislative act repealed part of the 1824 act and again required supreme court justices to travel the circuit. Because the state had four justices and five circuits, the legislature appointed one circuit judge for the circuit north of the Illinois River. In 1835, the legislature repealed the 1827 act and elected five circuit judges to perform circuit court duties. By 1839, the general assembly had created four new judicial circuits to provide for the increasing Illinois population. In 1841, the legislature created five new positions for justices on the Illinois Supreme Court, abolished the position of circuit judge, and divided the state into nine judicial circuits. The chief justice and the eight associate justices held circuit court in the circuit in which they lived.

The new constitution of 1848 provided for circuit courts with one judge in each of the nine circuits. Judges held at least two terms of court in each county each year. Qualified voters in each circuit elected judges, who served for a term of six years. All inferior court judges, including circuit judges, had to be citizens of the United States, had to reside in Illinois for at least five years and in their jurisdiction for at least two years, and had to be at least thirty years of age. The general assembly had the power to increase the number of circuits and added two circuits in 1849, four circuits in 1851, two circuits in 1853, seven circuits in 1857, and two circuits in 1859. By 1860, Illinois had twenty-six judicial circuits.

Court officials included clerks, sheriffs, coroners, deputies, state’s attorneys, and masters in chancery. According to the constitution of 1818, justices appointed a circuit clerk to document proceedings and to preserve complete records of all the decisions of the court. The position remained an appointed one until 1849, when the legislature provided for the election of a circuit clerk for a four-year term. The clerk could appoint deputy clerks to assist with his duties.

The first constitution provided for the election of a sheriff and coroner in each county for a term of two years. The sheriff executed all writs, warrants, processes, and proceedings that might be directed to him within the limits of his county. The sheriff also arrested those accused of crimes and kept them in jail until the next term of court. The coroner sometimes performed the sheriff’s duties if the sheriff was involved in a lawsuit or was unable to perform his duties. The sheriff attended the terms of courts and could appoint deputy sheriffs to assist with his duties.

The first Illinois General Assembly gave the governor the power to appoint state’s attorneys for each circuit. The attorney general acted as state’s attorney for the circuit that included the state capital. Each state’s attorney had to live in his circuit, where he prosecuted and defended all cases in which the state was a party. In 1835, the general assembly had the power to appoint state’s attorneys for each of the circuits and the attorney general. After the adoption of the new constitution of 1848, qualified voters in a circuit elected state’s attorneys for four-year terms, and the attorney general no longer performed the duties of state’s attorney on the circuit.

Each circuit court appointed a master in chancery for its county. The master in chancery took depositions, administered oaths, compelled the attendance of witnesses, executed judgments in chancery, and issued writs in the absence of the circuit judge. The master in chancery served for a term of four years until 1845, when the general assembly reduced the term to two years.

Inferior Courts

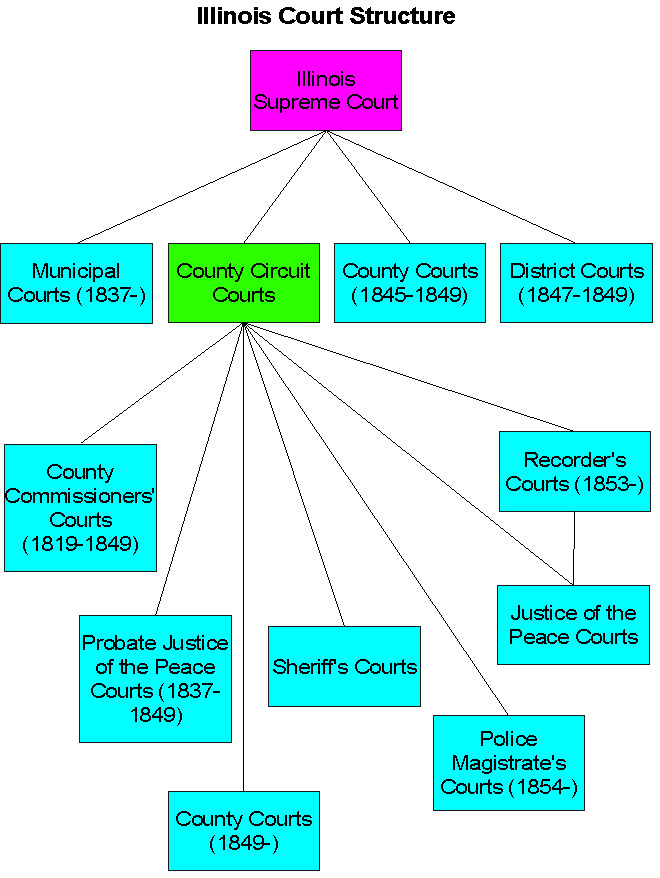

Both the 1818 and the 1848 constitutions gave the general assembly the power to create inferior courts. All courts below the supreme court were considered inferior courts. All of the inferior courts, except for the district court, existed in individual counties, municipalities, or districts, and did not cross jurisdictional lines. Most of the courts appealed their judgments to the county circuit court. However, some courts appealed their judgments directly to the supreme court.

County Commissioners’ Courts

In 1819, the first Illinois General Assembly created the county commissioners’ court. Each county had three commissioners, and two commissioners constituted a quorum. Qualified voters elected commissioners, who held office for a term of two years. In 1837, the legislature increased the term of commissioners to three years and provided for staggered elections to elect one commissioner every year. The commissioners appointed their own clerk until 1837, when the office became an elected position. The commissioners held four terms of court each year. The county commissioners’ court had jurisdiction throughout the county regarding county revenue, imposing and regulating county taxes, granting licenses, and managing public roads, canals, turnpikes, ferries, and bridges. The county commissioners’ court also had jurisdiction in all probate matters until the legislature created the probate court in 1821. The new constitution of 1848 abolished the county commissioners’ court, and the county court assumed jurisdiction of county business.

Justice of the Peace Courts

The constitution of 1818 directed the general assembly to appoint a competent number of justices of the peace in each county. The justice of the peace courts had jurisdiction over all debts in which the amount due on any contract, specialty, note, agreement for goods and merchandise, or agreement for labor did not exceed $100. The justice of the peace courts did not meet for regularly scheduled terms. The justice specified when a trial would be held, but it could be not less than five days nor more than fifteen days after issuing a summons. These courts allowed for speedy conflict resolution. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal their case to the circuit court. Since the justice of the peace could hold his court at any time, another of his functions was to hear criminal cases and hold over accused persons until the circuit court held its next term. The constable was the executing officer of the justice of the peace court. The justice documented and maintained his own records.

In 1826, the legislature provided for county commissioners to divide each county into districts with a minimum of two and maximum of eight. Qualified voters elected two justices of the peace in each district and three justices of the peace in the district that included the county seat. After 1835, county commissioners could increase the number of justices to any number to provide for a growing population. Justices of the peace held office for four-year terms. The legislature extended jurisdiction for justices of the peace periodically throughout the antebellum period to include trespass and trover when damages did not exceed $20, actions against sheriffs or constables when they had not paid execution money when damages did not exceed $100, attachment proceedings in sums not exceeding $50, trials for the right of property, and actions of forcible entry and detainer. In the 1830s, the general assembly incorporated cities and designated the mayor as a justice of the peace within the city limits. The new constitution of 1848 offered no substantive changes in the powers of the justice of the peace.

Sheriff’s Courts

The sheriff’s court was another inferior court that met as needed. In a lawsuit, a sheriff could seize the personal property of the losing litigant to satisfy the judgment. If any person other than the litigants claimed to own the property, he could sue the winning litigant for the right of property. The sheriff held a trial to determine ownership. The sheriff summoned jurors to hear the case and both the claimant and the winning litigant could call witnesses. If the jury found for the claimant, the sheriff would return the property to him. If the jury found for the winning litigant, the sheriff would sell the property to satisfy the judgment. Justices of the peace could also hold trials for the right of property. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal the decision of the sheriff’s court to the circuit court.

Municipal Courts

When the legislature incorporated the cities of Alton and Chicago in 1837, it established a municipal court in each city. The municipal courts had concurrent jurisdiction with the circuit courts in all civil and criminal matters. The Chicago Municipal Court had jurisdiction within the City of Chicago. The Alton Municipal Court had jurisdiction within all of Madison County and exclusive jurisdiction of all criminal matters within the city limits. The legislature appointed the municipal judges, who held court six times per year in Chicago and four times per year in Alton. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal their cases directly to the supreme court.

County Courts (1845-1849)

In 1845, the general assembly created the Cook County Court and the Jo Daviess County Court. The county courts had the same jurisdiction as the circuit courts within those counties in all matters civil and criminal. The general assembly appointed the county court judges, who held four terms of court each year. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal their cases directly to the supreme court. After the constitution of 1848 provided for a new and different county court, the general assembly changed the name of the Cook County Court to the Cook County Court of Common Pleas and the Jo Daviess County Court terminated and transferred its cases to the Jo Daviess Circuit Court. In 1855, the legislature created the Court of Common Pleas of the City of Cairo, which had jurisdiction within the city equal to that of the circuit court. In 1859, the general assembly changed the name of the Cook County Court of Common Pleas to the Superior Court of Chicago, which consisted of three justices who met monthly.

District Courts

In 1847, the legislature created a district court for each judicial circuit in the state. The judge of the circuit court also was the judge of the district court. The district court had jurisdiction in all criminal cases that occurred within the judicial circuit. When the governor of the state felt it was necessary to preserve law and order and to put down rebellions or mobs, he notified the district judge to call a term within thirty days. Jurors came from each of the counties in the circuit, and the state’s attorney prosecuted the cases. The judge appointed a marshal to carry out the process of court. If the district court interfered with a term of the circuit court, the circuit court stood adjourned until the next regular term of court. If the state’s attorney indicted the same person in both the circuit court and district court, he would enter a nolle prosequi in the circuit court. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal cases to the supreme court. The new constitution of 1848 did not provide for district courts, and the legislature transferred jurisdiction of the district court to the circuit court.

County Courts (1849-)

In 1848, the new constitution provided for the creation of county courts, which were different from the county courts that the legislature created in 1845. In 1849, the general assembly created the county courts to replace the county commissioners' courts. The county judge held court with two justices of the peace for the transaction of county business. The county judge had the power of a justice of the peace. County courts also had jurisdiction in probate matters and in criminal cases in which punishment by fine did not exceed $100. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal decisions to the circuit court. During the 1850s, the general assembly gave some county courts concurrent jurisdiction with circuit courts.

Recorder’s Court.

In 1853, the legislature created the Recorder’s Court of Chicago. This was an inferior court with the same jurisdiction as the circuit court in all criminal matters except treason and murder and all civil matters in which the demand did not exceed $100. The judge had a five-year term and held court every month. All justice of the peace appeals went to the recorder’s court except when a term of the circuit or common pleas court began earlier than the next term of the recorder’s court. In such cases, a person could appeal to any of the three courts. Appeals from the recorder’s court went to the circuit court. By the end of the 1850s, the general assembly created recorder’s courts in other cities.

Police Magistrate’s Courts

In 1854, the general assembly created the Police Magistrate’s Court. It was an inferior court of civil and criminal jurisdiction. The court had jurisdiction in all cases that arose under the ordinances of a town or city in which the demand did not exceed $100. Qualified voters elected one police magistrate for every six thousand residents up to a total of three magistrates. Police magistrates served four-year terms and were commissioned and qualified in the same manner as justices of the peace. Practice in the police magistrate’s court conformed to practice in justice of the peace courts. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal cases to the circuit court.

Probate Courts

The first Illinois General Assembly gave the county commissioners’ court jurisdiction concerning probate matters, such as proving wills and settling estates. In 1821, the legislature removed probate jurisdiction from the county commissioners' court and created the probate court to handle estate settlements. The probate judge for each county held court two times each month. The general assembly appointed the probate judges, who also had sole jurisdiction to hear and to determine all applications for discharge from imprisonment for debt.

In 1837, the legislature abolished the probate courts and created the probate justice of the peace courts. Qualified voters elected a probate justice of the peace, who had the same powers and jurisdiction in civil cases as other justices of the peace and held office for a term of four years. In 1845, the legislature reduced the term to two years. The probate justice of the peace had jurisdiction in all cases of debt in which the executor or administrator was a party and the demand did not exceed $1,000. The probate justice of the peace had the power to administer all oaths, to grant letters of administration, to prove wills, and to settle estates.

The constitution of 1848 provided for county courts with probate jurisdiction. Qualified voters in a county elected a judge, who held office for a term of four years. The judge held court monthly. The court had jurisdiction in all powers of probate court with concurrent jurisdiction with the circuit courts in all applications for sale of real estate of deceased persons and payment of debts. Qualified voters elected the county clerk, who also served as recorder of deeds for the county, for four-year terms. Dissatisfied litigants from all variations of the probate court could appeal decisions to the circuit court.

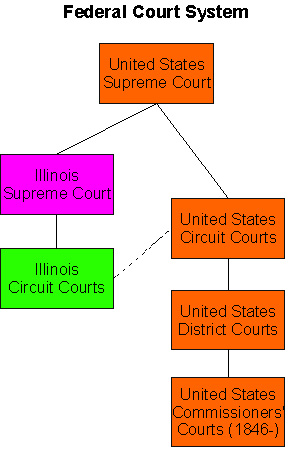

Federal Courts

The United States Constitution of 1787 provided for a Supreme Court and other inferior courts that Congress might create. The first Congress created circuit courts and district courts and assigned jurisdiction to all of the levels of the federal court system. The President nominated all federal justices, and the Senate confirmed the nominations. The United States Supreme Court consisted of a chief justice and five associate justices, who held office during good behavior. Congress increased the number of associate justices to eight in 1837. The Court had original jurisdiction in cases that involved ambassadors, mandamus, and cases in which a state was a litigant, and had appellate jurisdiction in all other cases. Congress also required that the justices travel the circuit and maintain contact with the local communities.

The federal court system had two tiers of trial courts. The higher tier was the circuit court. A Supreme Court justice and the district judge presided in the circuit court, which was the primary trial-level court in the federal judiciary system. The circuit court had concurrent jurisdiction with the state courts over all cases in common law or equity where the matter in dispute exceeded $500, and jurisdiction in cases where the United States was a plaintiff, and in cases between citizens of different states. Circuit courts could hear patent infringement cases without regard to citizenship or amount. Circuit courts also had jurisdiction over all crimes and offenses cognizable under the authority of the United States. Litigants in a state court case could petition to move the case to the federal circuit court if the opposing litigants were from different states or the matter in controversy exceeded $500. The circuit court also acted as an appellate court and heard appeals from the district court.

The lower tier was the district court. A district judge presided over the district court. Federal district boundaries coincided with state boundaries, and several districts comprised a circuit. District courts had jurisdiction in all crimes and offenses under the authority of the United States where punishment involved whipping under thirty stripes, a fine under $100, or imprisonment under six months. District courts also had exclusive jurisdiction of all admiralty and maritime cases. When Congress passed the Bankruptcy Acts of 1800 and 1841, it assigned jurisdiction to the district courts. Dissatisfied litigants could appeal admiralty cases to the circuit court in matters exceeding $300 and could appeal all other cases to the circuit court by a writ of error as long as the matter in controversy exceeded $50.

After Illinois became a state in 1818, Congress created the District Court for the District of Illinois. The Illinois district court had the full jurisdiction of a circuit court because Congress did not place Illinois in a circuit. The President appointed one judge who resided in the district and held court twice a year in the state’s capital. The judge appointed a clerk to keep the records of the court. The President also appointed a district attorney and a marshal. In 1837, Congress reorganized the circuit court system and added three new justices to the United States Supreme Court. At that time, Illinois became part of the seventh circuit, which also included the districts of Ohio, Indiana, and Michigan. The district court of Illinois lost its jurisdiction as a circuit court and assumed the regular jurisdiction of district courts. The circuit court held two terms each year, but the Supreme Court justice had to attend only one of the terms. Judges held court in Vandalia, the state capital, until 1839, when the capital and the federal courts moved to Springfield.

Rising population in the northern part of the state, particularly in Chicago, produced the need for an additional term of federal court. Congress authorized an annual term for the circuit and district court of Illinois in Chicago beginning in July 1848. In 1851, Congress provided for a second term in Chicago, giving the district of Illinois four terms of federal court each year. In 1854, Congress divided the state into two judicial districts—the Northern District of Illinois, which held court in Chicago, and the Southern District of Illinois, which held court in Springfield. The judge for the District of Illinois transferred to the Northern District, and the records of the court went to the Northern District as well. In 1856, Congress authorized the clerk of the Southern District to make transcripts of all the proceedings from the records of the Northern District that pertained to land titles or cases that began in what became the Southern District.

Congress established the position of United States Commissioner in 1793 to admit persons accused of federal crimes to bail. The circuit court justice appointed the commissioner, who had to be “learned in the law.” In 1812 and 1817, the legislature expanded the powers of the commissioner to take depositions and affidavits. In 1846, Congress gave judicial functions to the commissioners, effectively making them justices of the peace for the federal court system. Commissioners had the power to arrest offenders, try them, or hold them over until the next term of the circuit court. When Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, it conferred upon the commissioners concurrent jurisdiction with the other federal courts to hear fugitive slave cases. Since commissioners held court only when necessary, claimants of fugitive slaves often petitioned the commissioner to try their cases.

Court officials were important members of the federal court system. The marshal was the executive officer of the federal courts corresponding with the sheriff of a county. Each judicial district had a marshal, whom the President appointed for a term of four years. The marshal served summonses and subpoenas, held criminals for trial, and executed judgments. The marshal could appoint deputy marshals to assist him with his duties. The district attorney prosecuted people indicted for criminal offenses and served as attorney for the United States in civil cases. Each judicial district had a district attorney, an individual “learned in the law,” whom the President appointed for a term of four years. The circuit clerk and the district clerk were separate positions but each performed the same functions for their respective courts. The justice or judge appointed the clerk, who served during good behavior. The clerk kept and maintained the records and proceedings of the court and could appoint deputy clerks to assist him in his duties. The federal courts also had a master in chancery, who had the power to take depositions, to compel the attendance of witnesses, and to execute judgments in chancery.

Bibliography

Laws of Illinois

Laws of Illinois Territory

Laws of Indiana Territory

Laws of the Northwest Territory

United States Statutes at Large

See Legal History Bibligraphy for references to books with more detail on courts and court structure.